In times where immigrants are seen as a problem by many in Western societies, a developed country in East Asia highlights the importance of immigration and its benefits to society through a lack thereof.

While its northern neighbor is usually depicted as the main foe of the Republic of Korea, another grave threat to South Korea’s population is of a domestic nature. One far slower and less eye-catching than missile launches, but equally pervasive in its disruption of society. The lack of new life.

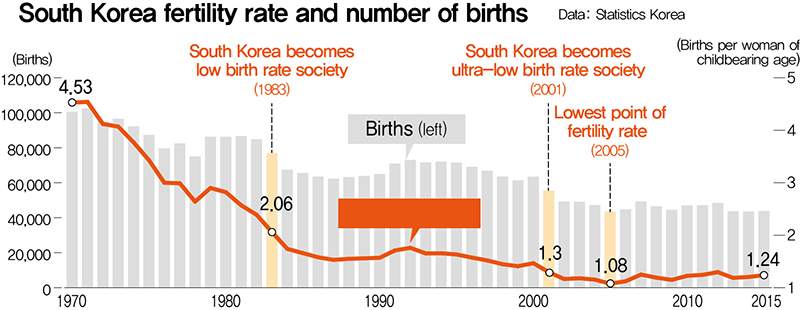

Although South Korea will be the first state worldwide in which average life expectancy of women will break the barrier of 90, a study in 2014 claimed the country would face natural extinction by 2750 if the trend of its low birth rates, set in motion in the 1970s, continues. While the notion of complete extinction may be somewhat exaggerated, the threat of serious population decline within mere decades is all too real. Low numbers of births and a rapidly ageing community pose a serious demographic and social-economic challenge to Korean lawmakers.

The demographic prospects of the East Asian nation have been dismal for many years. According to the latest report on social indicators by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Korea holds the lowest fertility rate of all OECD countries. In 2014, Korean women were expected to have 1.21 children in their lifetime, lower than the OECD average of 1.7 and, more importantly, below the rate necessary to keep the population size constant. Moreover, first-time mothers in Korea have the highest average age in the OECD region, 31 versus 28.7 years.

Maintaining the population at constant or even growing levels can be achieved by increasing the number of births in the country and through immigration. So far, Korean governments have opted for the former, attempting to increase the number of births through the adoption of various policies.

During the Roh Moo-Hyun government (2003-2008), the interrelated problems of low fertility rates, an ageing society and population size in South Korea were first recognized. A presidential committee was set up in 2004 to devise solutions. The committee announced in 2006 a five-year ‘Low Fertility and Ageing Society’ plan for the period 2006-2010, during which 19.7 trillion KRW (17.8 billion USD) was spent on increased support for childcare and education and policies to improve income security and medical care for the elderly. A second five-year plan, drafted during the next Lee Myung-Bak government (2008-2013), appeared in 2011, expanding previous policies and introducing other multi-faceted countermeasures. The plan, covering the period 2011-2015, allocated a total of 60.5 trillion KRW (63.4 billion USD) to raise the declining birth rates.

To some avail. As shown in the figure above, Korea’s fertility rate hit an absolute low of 1.08 in 2005, and has since only marginally increased. It is still below the level of 1.3 though, the threshold below which a country is considered to experience ‘lowest low fertility.’ Despite government action, South Korea has been trapped since the turn of the millennium (when fertility rate hit 1.47) in this category. In 2015, a record-low number of births was recorded (8.6 new babies per 1,000 South Koreans), and predictions for 2016 are even worse. Other notorious low fertility countries like Italy and Japan, while still struggling, have had more success in leaving the ‘lowest low fertility’ category.

There is a threat of extinction if the government does not pursue other options.

Some researchers predict the fertility rate will increase within a decade to about 1.7, bringing it to similar levels of countries like The Netherlands and Canada. But even such a significant increase would be insufficient to maintain South Korea’s population size. The so-called ‘replacement fertility’ rate has commonly been accepted to be around 2.1.

On top of that, the distribution of age cohorts in the country is expected to take on worrisome shapes in the coming years. Over the past four decades, no other developed society has seen a similar demographic shift as extreme like South Korea’s, as its population has aged the fastest among all OECD countries. An OECD report in 2014 notes, “In 2050, Korea is projected to have only 1.4 people of working age for every person over the age of 65.”

These demographic trends spell trouble for Korea’s economic productivity and growth as well as its military, threatening a clear decline in military manpower. Moreover, the country’s provisions for the elderly are still poor. Social spending as part of its GDP the past years has been about 10 percent, less than half of the OECD average. And poverty in Korea is mainly concentrated among older Koreans, as 49 percent of Koreans aged 65+ lived below the poverty line compared to 13 percent on average of elderly in OECD countries.

Given these numbers, and the government’s failed efforts at significantly increasing fertility rates, it seems policymakers should embrace the other solution of maintaining its population size and counter the trend of its ageing population. Immigration.

South Korea is one of the world’s most ethnically homogeneous societies. About 2 million foreign nationals were registered in 2016, accounting for 4 percent of the entire population. More than half (51.4 percent) were Chinese, while other major represented countries of origin were the U.S. (7.4 percent), Vietnam (7.1 percent), and Thailand (4.5 percent). About 1.5 million out of those 2 million are long-stay foreign residents. The total number of foreign residents, while in relative terms still low, has been steadily increasing by roughly 10 percent annually over the past three decades. Starting from about 50,000 in 1990 to half a million in 2000, and hitting the 1 million mark in 2006.

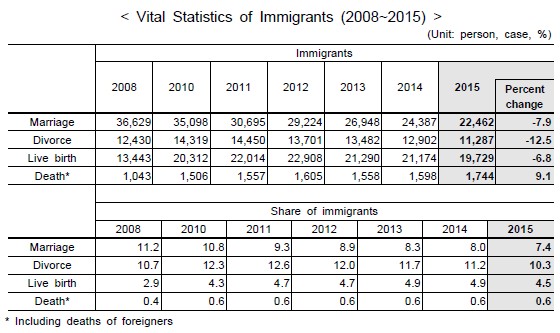

A portion of this increase in Korea’s foreign population is the result of marriage migrants, whose countries of origin used to be mainly East Asian-based (China and Vietnam) but are increasingly diversified. While total number of marriages of immigrants have been on the decline in recent years, representing 7.4 percent of all marriages in 2015, perhaps more interesting is the rising share of immigrant births, increasing from 2.9 percent in 2008 to 4.5 percent in 2015. Moreover, an estimated third of all children born in 2020 are expected to be of part Korean and part other Asian descent, colloquially known as ‘Kosian,’ and following current trends, about 10 percent of the population will be composed of foreign-born and immigrant families by 2030.

While promising statistics, without additional government efforts it will not be sufficient to successfully counter Korea’s demographic crisis. A report by a private Korean think tank concluded the country would need more than 15 million immigrants by 2060 in order to sustain its growth.

The ethnocentric character of Korean society has long been an obstacle to immigration. An editorial by The Korean Times on embracing more immigrants specifically calls out Koreans’ entrenched xenophobia and antagonism toward immigrants. While there are still divergent views about immigration in Korean society, a study in 2014 concluded a majority of younger and better-educated citizens has “a generally positive view of immigrants and immigration,” though a sizeable minority of older and less-well educated citizens still exists which is wary of immigration and its effects.

Though gradually decreasing, racial discrimination is still high by global standards. According to the most recent available data in 2010 of the World Values Survey, 34 percent of Koreans felt negatively about their neighbors being of different ethnicity, and 44 percent felt negatively about migrant workers. A 2014 Korean research publication highlighted a worrying trend of decreasing acceptance of multicultural families in recent years, in particular among women and those in their 20s and 30s.

While Korean policymakers have increasingly backed a push for a more multicultural society and welcoming of immigrants, their approach to an embrace of multiculturalism mainly relies on assimilation without social integration. To reduce discrimination against foreigners, a better understanding of immigrants and immigrants cultures among Koreans has to be promoted. Given the need for millions of immigrants to sustain society, the government should encourage programs to change attitudes of Koreans, if it wants to prevent major societal rifts. As one of the organizers of such a program noted, South Korea’s historical lack of experience living with people of other ethnicities is problematic because it is easier “for prejudices to take hold,” like “the idea that the rate of criminality among foreigners is much higher.”

While Korean policymakers have increasingly backed a push for a more multicultural society and welcoming of immigrants, their approach to an embrace of multiculturalism mainly relies on assimilation without social integration. To reduce discrimination against foreigners, a better understanding of immigrants and immigrants cultures among Koreans has to be promoted. Given the need for millions of immigrants to sustain society, the government should encourage programs to change attitudes of Koreans, if it wants to prevent major societal rifts. As one of the organizers of such a program noted, South Korea’s historical lack of experience living with people of other ethnicities is problematic because it is easier “for prejudices to take hold,” like “the idea that the rate of criminality among foreigners is much higher.”

If policymakers are successful in softening Korea’s ethnocentric culture and replace it with a more multicultural-friendly environment, policies aimed at attracting more immigrants will undoubtedly be more successful. To start with, the government should discard the policy where dual citizenship (only widely introduced since 2011!) holders are not allowed to vote, run for public office, seek employment in the public service, and serve in the military. Doing so will not only attract more immigrants in the long run but also increase integration of foreigners in society.

Korea could, moreover, be more open to taking in refugees, as the number of displaced people worldwide is at an unprecedented high. Its refugee policy has been extremely restrictive, and stands, according to a Human Rights Watch representative, in stark contrast to the generous resettlement package offered to North Korean defector.

Finally, while promoting an influx of immigrants obviously serves a functional demographic goal to Korea’s economy and society, policymakers could make more effort at ‘humanizing’ immigrant workers and protecting their rights. A report by Amnesty International in 2014 highlighted the exploitation and abuse of thousands of migrant agricultural workers, enabled by the government’s unwillingness and disregard to reform its immigration system and laws.

While the benefits of immigration and its necessity seem to be generally accepted in society and among Korean politicians, it is clear that much still needs to be done to successfully combat its demographic crisis. The decline in Korea’s labor force and overall population can only be countered by a coordinated effort of policymakers to increase the immigrant population and an integral approach to its social inclusion, fostering a dynamic, creative and sustainable economy. For without immigrants, there is no South Korean future.